Key Highlights

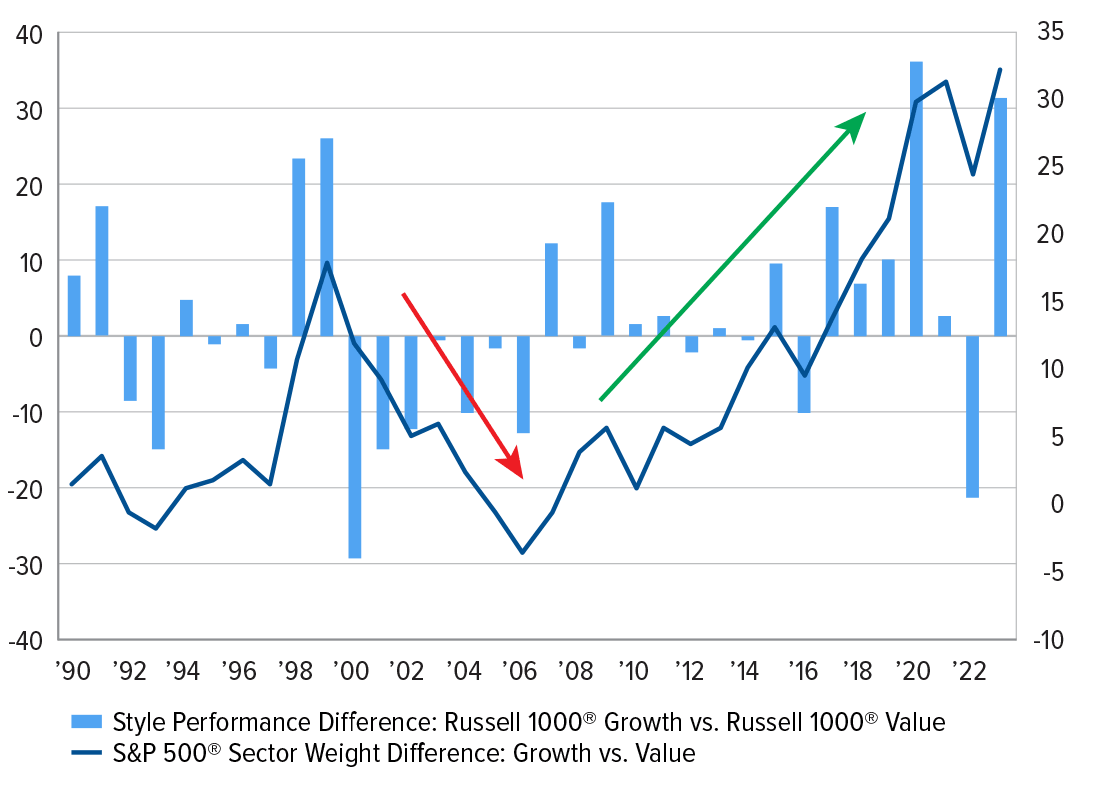

- Value and growth investing tends to rotate in cycles, and many seem to have studied them superficially.

- Value-growth investing should stretch well beyond mathematical and statistical models, as qualitative factors also can influence investment outcomes.

- Macroeconomic conditions affect value and growth sectors and companies differently.

- Government regulations and policies can greatly affect sector fundamentals.

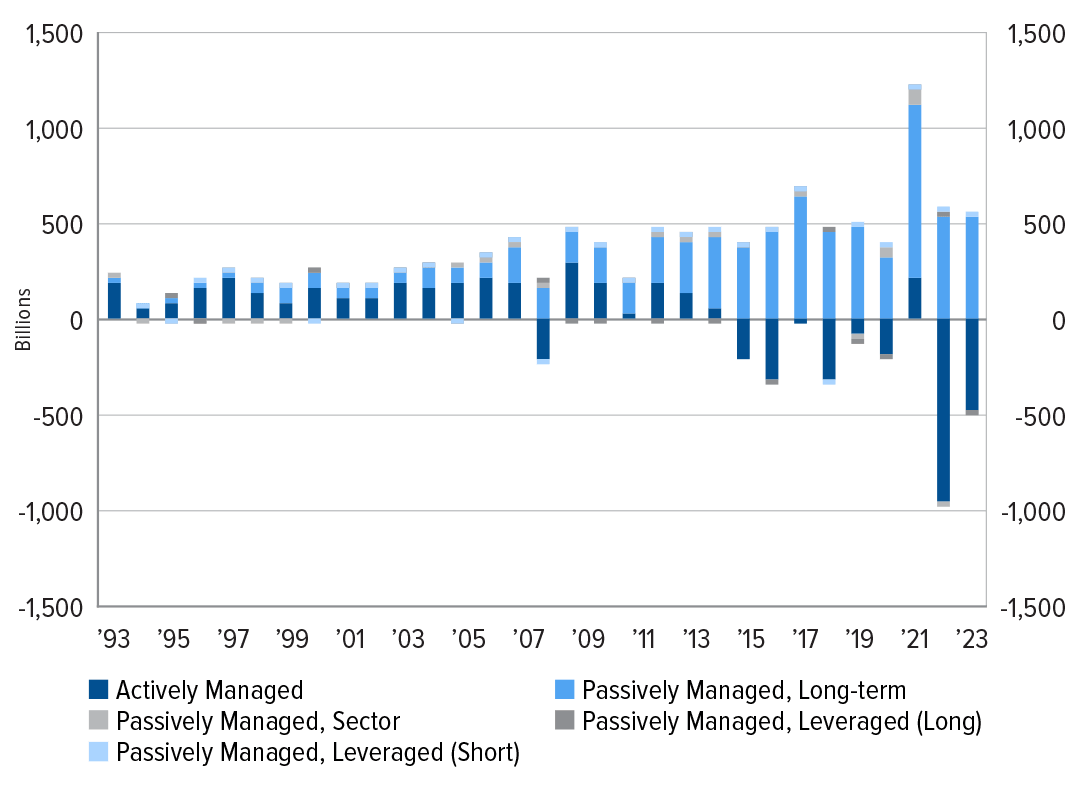

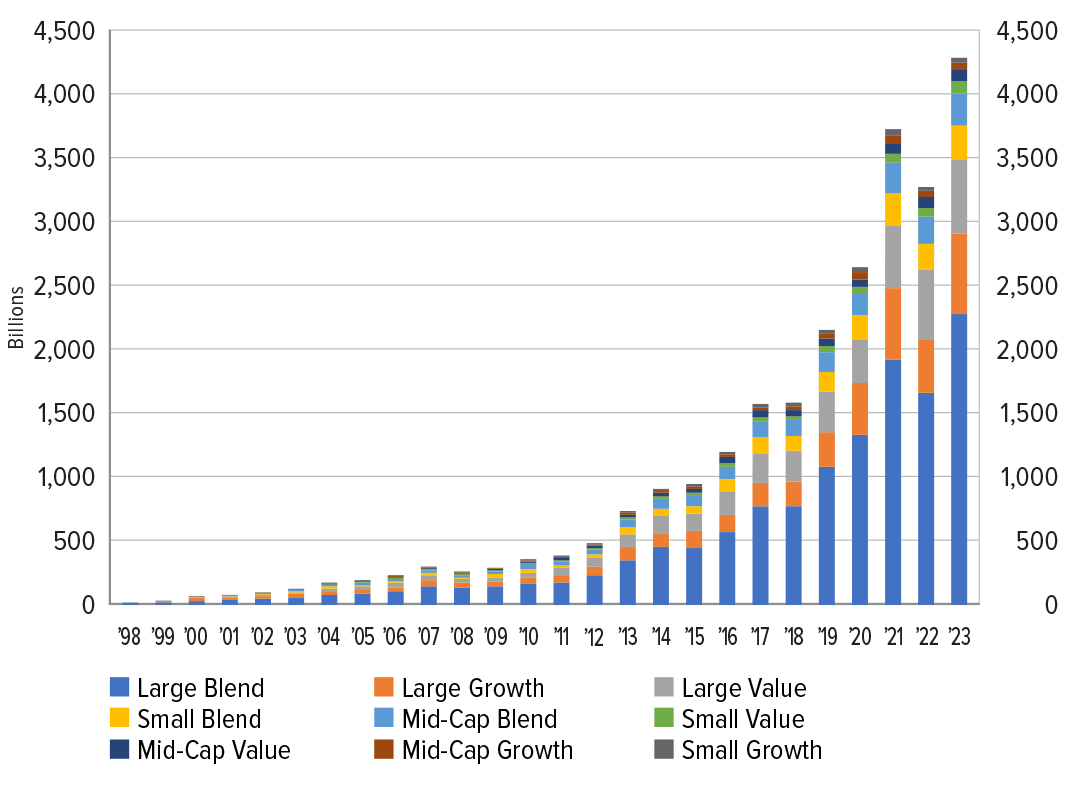

- The evolution between active and passive investing also influences style and factor trends.

U.S. Value-Growth Background

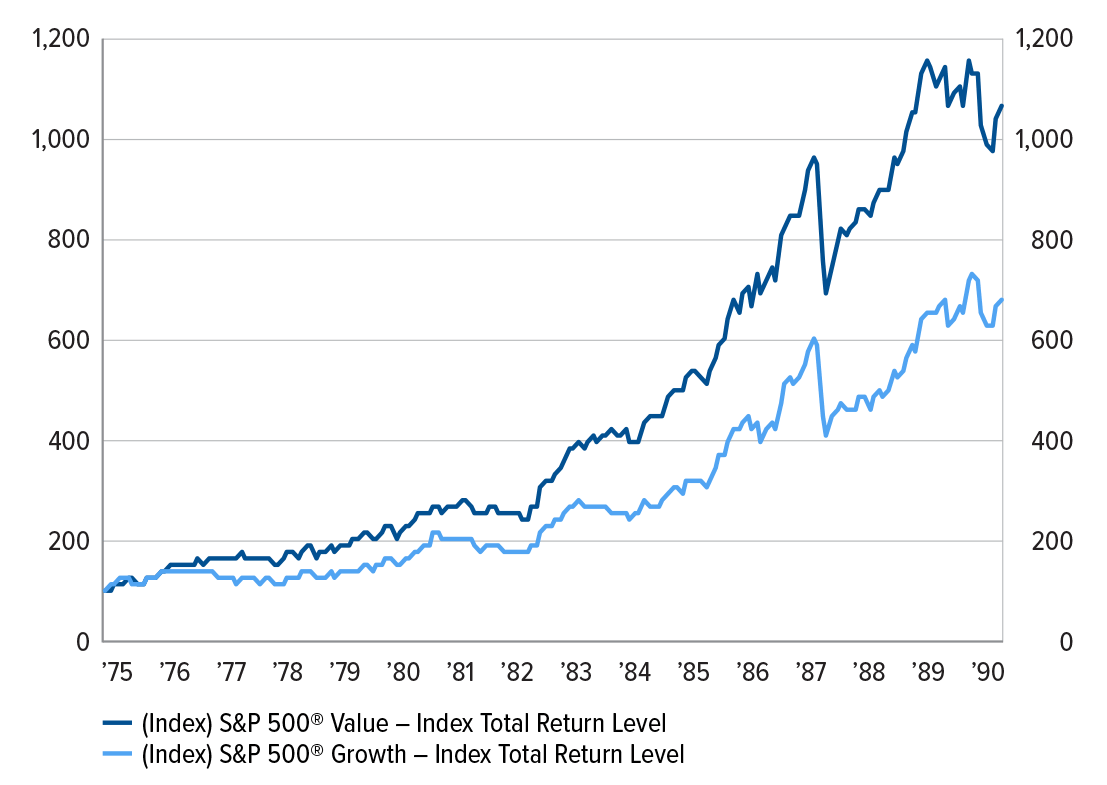

While growth stocks have handily outpaced value stocks over the past decade, there were periods when the latter outperformed the former by a good stretch. In fact, multiple studies show value investing may be the preferred method over a long-term period. For example, the Fama-French three-factor model is a statistical model designed by renowned Nobel laureates, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French. The model found that value stocks outperform growth stocks over the long term, and it has long been part of the framework behind portfolio management and asset pricing.

But despite the academic research, we still experience periods when growth stocks greatly outperform value stocks. We typically see this occur when innovative technologies generate excitement, including the dotcom boom period and perhaps the current one driven by artificial intelligence (AI).

Though academic research is important, real-life portfolio management stretches well beyond the three factors typically measured (i.e., size, valuation, and overall market risk). For instance, regulatory environments can drive or hinder sectors. Furthermore, with the tremendous growth in passive investing, there has been a great shift of influence toward index providers such as Standard and Poor’s (S&P) and its prominent S&P 500® Index.

Performance—Value vs. Growth

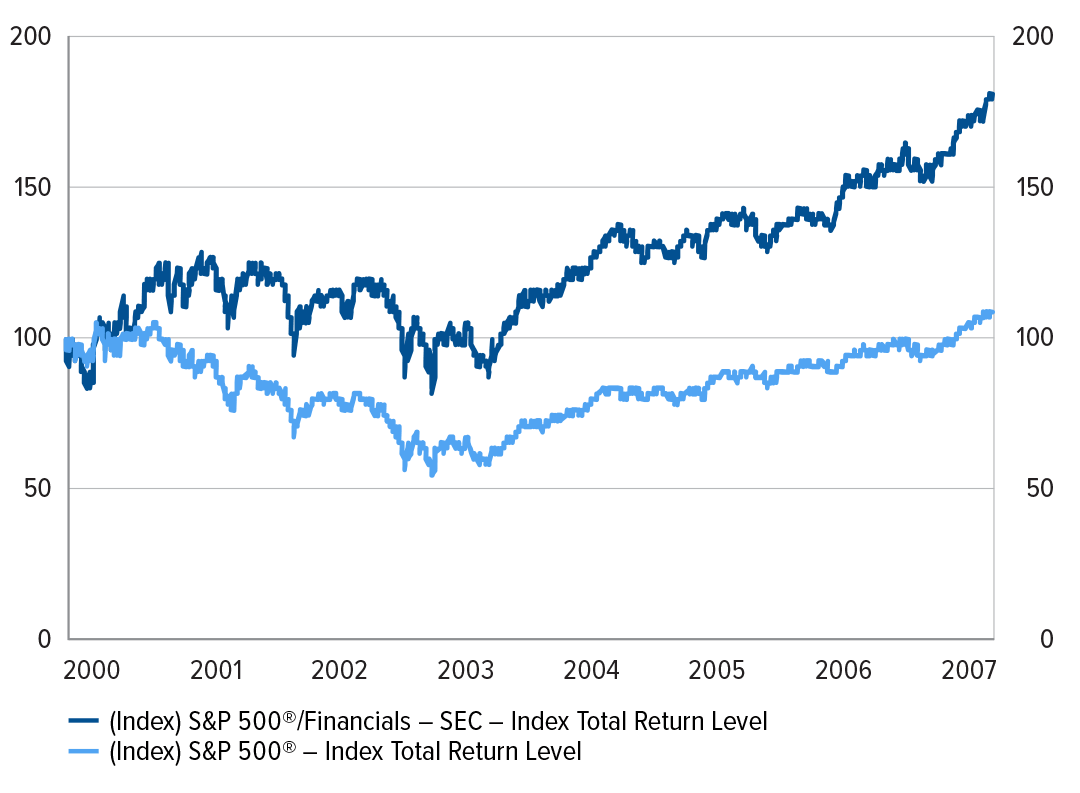

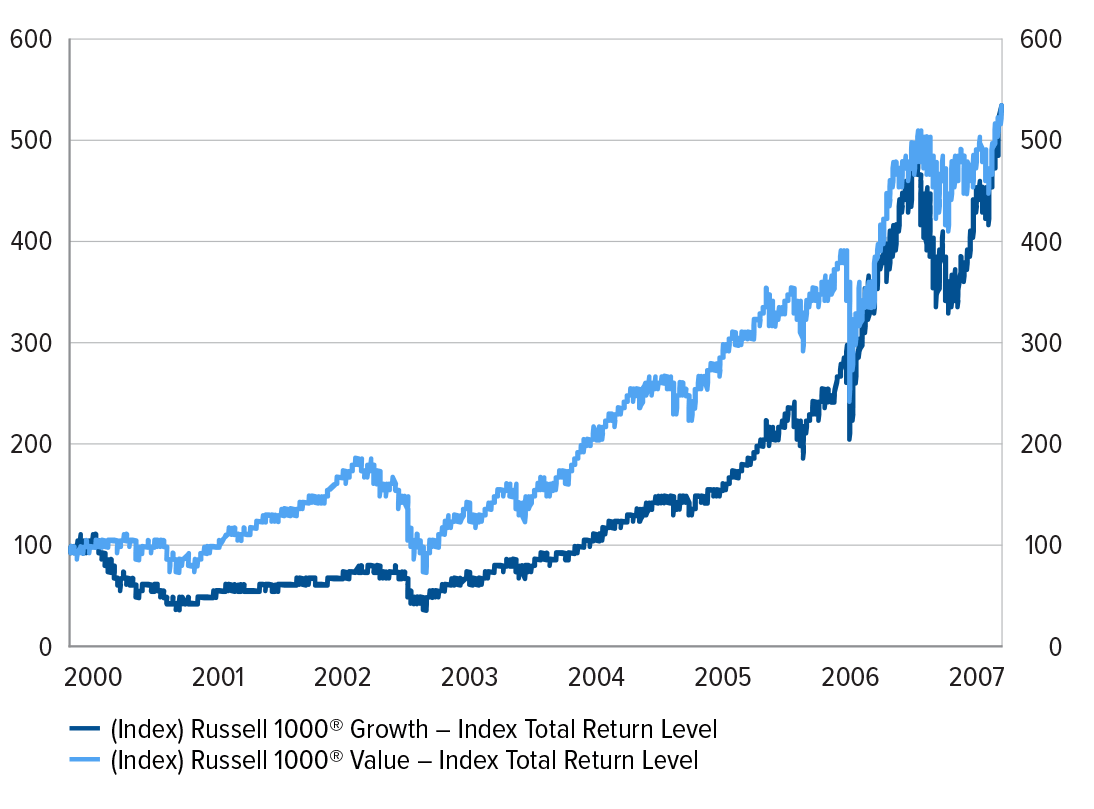

Macroeconomic regimes change over time, so sampling different periods may yield contrasting results. If one was to conduct a study between 1975 and 1990, one may conclude that value stocks tend to outperform growth stocks over the long-term. It should be noted that for performance purposes, we used the S&P indices for the following chart, as they have a longer track record than the Russell indices.Chart 1: EME outperformed the S&P 500® index from 2001 to 2007